UsingDC

- Creator: Stefanie Rühle

- Contributer: Tom Baker and Pete Johnston

Purpose and Scope of this Guide[edit]

"The Dublin Core" (aka the Dublin Core Metadata Element Set), created in 1995, is a set of fifteen generic elements for describing resources. These are: Creator, Contributor, Publisher, Title, Date, Language, Format, Subject, Description, Identifier, Relation, Source, Type, Coverage, and Rights. Today the Dublin Core is a formal standard [1][2][3], used in countless implementations, and one of the top metadata vocabularies on the Web.

But "Dublin Core metadata" is about more than fifteen elements. It is best described as a style of metadata that has evolved from efforts to put the fifteen elements into the context of a coherent approach to metadata on the World Wide Web generally. Since the late 1990s, the Dublin Core style has evolved in the context of a Dublin Core Metadata Initiative (DCMI) -- now incorporated as a non-profit organization hosted at the National Library Board of Singapore -- in tandem with a generic approach to metadata developed in the World Wide Web Consortium under the banner "Semantic Web". The Semantic Web approach achieved a breakthrough in 2006 with the Linked Data movement, which uses DCMI Metadata Terms as one of its key vocabularies. "DCMI Metadata Terms" is a larger set that includes the fifteen elements along with several dozen related properties and classes. "Dublin Core application profile" is the key expression of the Dublin Core style. An application profile uses DCMI metadata terms together with terms from other, more specialized vocabularies to describe a specific type of information -- and it does this in the framework of the Semantic Web.

These guidelines provide an entry point for users of Dublin Core -- i.e., for users of DCMI Metadata Terms in the "Dublin Core style". For catalogers, it will show how to create metadata "descriptions" for information resources such as documents, images, data, etc. Implementers will it support publishing Dublin Core Metadata as Linked Data. The guidelines will neither show how to create a Dublin Core Application Profiles -- for this see the Guidelines for Dublin Core Application Profils -- nor how to express Dublin Core Terms in different syntaxes (e.g. xml) -- for this see the section "Syntax Guidelines" of DCMI Specifications. According to this the User Guide contains the following sections:

- UsingDC: a short introduction about Dublin Core and Dublin Core Terms

- CreatingMetadata: a description how to create content for DCMI Metadata illustrated by examples

- PublishingMetadata: a description how to use Dublin Core Metadata as linked data illustrated by examples

What is Metadata?[edit]

Metadata has been with us since people made lists on clay tablets and scrolls. The term "meta" comes from the Greek for "alongside" or "with". Over time, "meta" was also used to denote something transcendental, or beyond nature. "Meta-data", then, is "data about data", such as the contents of catalogs, inventories, etc. Since the 1990s, "metadata" denotes machine-readable descriptions of things, most commonly in the context of the Web. The structured descriptions of metadata help find relevant resources in the undifferentiated masses of data available online. Anything of interest can be described with metadata, from book collections to football leagues and stuff you want to sell. Describing different types of resources requires different types of metadata and metadata standards.

What is Dublin Core?[edit]

In the mid 1990s Dublin Core started with the idea of "core metadata" for simple and generic description of electronic resources. An international, cross-disciplinary group of professionals from librarianship, computer science, text encoding and museum community, and other related fields of scholarship and practice developed such a core standard – the fifteen Dublin Core elements. But this was just the first steps – since then the World Wide Web has changed in some ways and has broken new ground on the way to a semantic web. Dublin Core followed this path developing further standards for metadata based on the World Wide Web Consortium's work on a generic data model for metadata, the Resource Description Framework (RDF). At the same time the scope of Dublin Core metadata was broadened from "electronic resources" to encompass, in principle, any object that can be identified, wether electronic, real-world, or conceptual, and particularly including resources of the sort named in the DCMI Type Vocabulary.

So Dublin Core metadata standards today are:

- The DCMI Abstract Model (DCAM) – an RDF based syntax independent model supporting mappings and cross-syntax translations.

- The Sinagpore Framework for Dublin Core Application Profiles – a framework which defines the components that are necessary for documenting a Dublin Core compatible Application Profile.

- The Dublin Core Metadata Vocabularies

- DCMI Metadata Terms in the /terms/ Namespace

- DCMI Type Vocabulary

- Metadata terms related to the DCMI Abstract Model

- Dublin Core Metadata Element Set, Version 1.1

Dublin Core Terms[edit]

The Dublin Core Metadata Vocabularies distinguish four types of terms: properties, classes, datatypes and vocabulary encoding schemes.

- Dublin Core Properties resp. Elements are the "core" attributes of resources, used for the uniform structured resource description. Properties like dc:title, dc:creator, etc. are defined in the Dublin Core Metadata Element Set (DCMES), which is the Set of the fifteen generic elements created in the 1990s. And properties like dcterms:title, dcterms:alterantive, etc. are defined as [1] DCMI Metadata Terms - also known as subproperties or refinements of the DCMES. In record based metadata systems properties are usually called metadata fields.

- Classes are groups of resources having certain properties in common and therefore put together as members of one concept. Dublin Core Classes are the terms of the DCMI Type Vocabularies - e.g. dcmitype:Collection, dcmitype:dataset, etc. Dublin Core also defined [ http://dublincore.org/documents/dcmi-terms/#H6 Classes as DCMI Metadate Terms] - e.g. dcterms:Agent, dcterms:BibliographicResource, etc. Relationships between Dublin Core Classes and Properties are the following:

- Each property may be related to one or more classes by a has domain relationship, where the domain indicates the class of resources that the property should be used to describe.

- Each property may be related to one or more classes by a has range relationship, where the range indicates the class of resources that should be used as values for that property.

- For further information about domains and ranges used with DCMI Properties see Domains and Ranges for DCMI Properties

- Datatypes resp. Syntax Encoding Schemes (SES) are the rules that specify how a value has to be structured. Dublin Core defined Syntax Encoding Schemes as DCMI Metadata Terms - e.g. dcterms:W3CDTF for date specification. The relationship between Dublin Core datatypes and properties is as follows:

- Certain properties - e.g. date, identifier, etc. - may be typed by a Syntax Encoding Scheme, where the Syntax Encoding Scheme dictates the syntax of the values used with that property.

- A Vocabulary Encoding Scheme (VES) resp. Concept Scheme identifies controlled vocabularies - such as thesauri, classifications, subject headings, taxonomies, etc. - whose terms may be used as values. The relationship between Dublin Core vocabulary encoding schemes and properties is as follows:

- Certain properties - e.g. subject, coverage, etc. - may be constrained by a Vocabulary Encodings Scheme, where the Vocabulary Encodings Scheme dictates what values may be used with that property.

This User Guide describes the usage of Dublin Core Properties and their relation to Classes, Syntax Encoding Schemes and Vocabulary Encoding Schemes. Therefore it lists all properties defined in the following two namespaces of DCMI Metadata Terms:

- http://purl.org/dc/elements/1.1/ (referred to here using the short prefix "dc:")

- http://purl.org/dc/terms/ ("dcterms:").

and illustrate their usage by examples. Examples are offered for two points of view: for the "cataloger" creating metadata descriptions, typically with help from a software interface, and for the "technician" responsible for publishing the data created as linked data.

- CreatingMetadata: describes how to create content for DCMI Metadata listing each property by name, abbreviated URI, and definition, and groups together related properties -- i.e. properties that can be described with similar usage guidelines and illustrated with similar examples.

- PublishingMetadata: describes how to use DCMI Metadata as linked data listing the properties by namespaces.

- The terms namespace

- used with literal values

- used with non-literal values

- The legacy or element namespace

- The terms namespace

The guide does not regard information about the usage of Dublin Core Properties with different syntaxes. For this see:

- Expressing Dublin Core metadata using the Resource Description Framework (RDF)

- Guidelines for implementing Dublin Core in XML

- Expressing Dublin Core Description Sets using XML (DC-DS-XML)

- Expressing Dublin Core metadata using HTML/XHTML meta and link elements

- Expressing Dublin Core metadata using the DC-Text format

Dublin Core URIs and namespaces[edit]

Each Dublin Core Term has to be assigned a name that is unique in the context of a particular DCMI term set - e.g. abstract - and a URI of a DCMI namspace which is a globally unique identifier for that term - e.g. http://purl.org/dc/terms/abstract.

The DCMI Namspace Policy defines a DCMI Term URI as "the URI for a term that is declared and managed by DCMI" and a DCMI Namespace as "a collection of DCMI term URIs where each term is assigned a URI that starts with the same base URI. The base URI is known as the DCMI Namespace URI. (Note that a DCMI namespace is not the same as an 'XML namespace')." The policy defines the following four base URIs:

- http://purl.org/dc/elements/1.1/ for the fifteen properties of the Dublin Core Metadata Element Set - called the legacy namespace

- http://purl.org/dc/dcmitype for classes in the DCMI Type Vocabulary - called the type namespace

- http://purl.org/dc/dcam for terms used in the DCMI Abstract Model (of which there are currently two)

- http://purl.org/dc/terms/ for all other DCMI properties, classes, vocabulary encoding schemes and datatypes - called the terms namespace

To ensure interoperability and persistence all DCMI URIs dereference to machine-processable DCMI term declarations, representing one or more DCMI terms.

What is Linked Data?[edit]

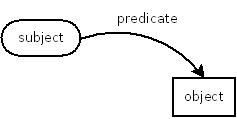

Linked Data is a method of exposing, sharing, and connecting data on the Semantic Web using URIs and RDF (see http://linkeddata.org/). Metadata are the backbone of this method, making statements about data and how they relate to each other. In Linked Data these statements have to be expressed in RDF triples, which break statements in three parts:

- the subject - the part that identifies the thing the statement describes,

- the predicate - the part that identifies a property of the described thing.

- the object - the part that identifies the value this property has when describing this thing.

(see: http://www.w3.org/TR/2004/REC-rdf-primer-20040210/#statements)

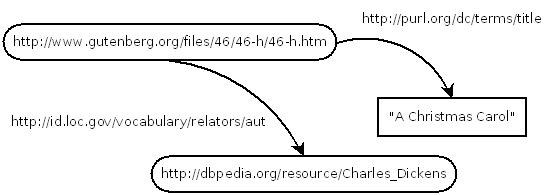

Another "must" when publishing metadata in Linked Data is the usage of URIs. In Linked Data you need URIs referencing to things by identifying, localizing and interlinking them. Considering this a triple graph describing Charles Dickens "A Christmas Carol" might look this way:

Here the value "A Christmas Carol" is a simple string or literal value. Another sort of values used in a triple are non-literal values, which means you use a URI that references to another description - the description of a thing that is the object of your statement. In our example the dbpedia URI of Charles Dickens references to such a description.

Based on the above said a metadata description in Linked Data consists of:

- a reference to a described resource, i.e. to the thing that the metadata is about, the subject of the metadata. This reference takes the form of a Uniform Resource Identifier (URI) or of an unnamed placeholder that is inferred by context (e.g., that metadata embedded in a document is about the enclosing document).

- references to properties: typed relationships between the described resource and various bits of descriptive information, or between the described resource and another resource. Examples of properties, which are also known as predicates, include the fifteen elements of the Dublin Core.

- values: bits of descriptive information (string literals) or references to other entities (resources), such as people or concepts, which are related to the described resource via the properties.

- references to classes, i.e. to types, or categories, of things, such as the category books or the category people.

- references to syntax encoding schemes (RDF datatypes), i.e. specifications of how value strings map refer to things in the world, such as 2010-09-24, which uses the YYYY-MM-DD pattern specified in ISO 8601 to represent the date 22 September 2010.

- references to vocabulary encoding schemes (VES), enumerated sets of resources of which the things referenced as values are members, the way a subject heading belongs to the VES Library of Congress Subject Headings.

- language tags indicating the language of words used in literal string values.

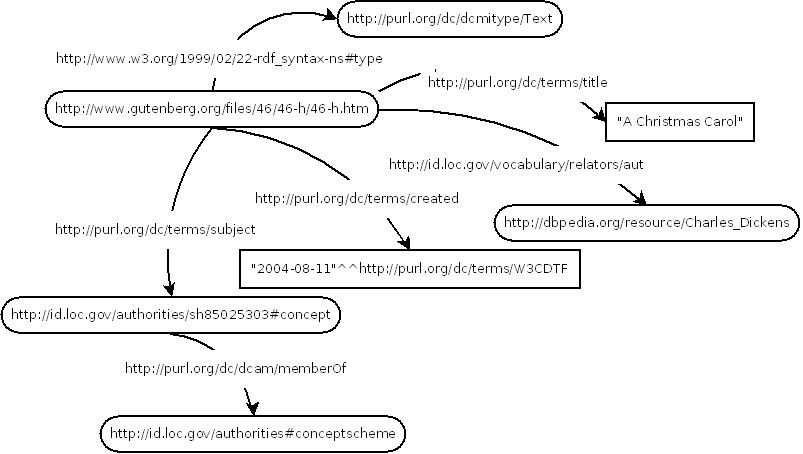

In a RDF graph this might look this way:

In this example the described resource is a web page referenced by the URI http://www.gutenberg.org/files/46/46-h/46-h.htm. We may reference to a class - in our example its the class "text" of the Dublin Core Type Vocabulary - using the property type. Further properties of the resource are "title", "author", "created" and "subject". We used literal - "A Christmas Carol" and "2004-08-11" - and non-literal values - <http://dbpedia.org/resource/Charles_Dickens> and <http://id.loc.gov/authorities/sh85025303#concept>. Literal values may be constrained by datatypes. In our example values describing dates are conform with W3CDTF. A language tag can be used to describe the language of a literal value (in our example the value of the title is English). Non-literal values may be constrained by vocabulary encoding schemes. In our example the value used describing the topic of the resource is a concept of the Library of Congress Subject Headings. This relation is specified by the property memberOf.

Dublin Core and Linked Data[edit]

Since the emergence of the Semantic Web and Linked Data approaches, implementers face a wider range of choices in designing applications. Traditional approaches based on metadata records and descriptive tags embedded in Web pages remain effective alternatives within closed, controlled implementation environments, while Linked Data approaches are designed to provide metadata in a generic form that is easily reusable by other applications for "mashing up" your data with related data published by others. Linked Data has given new meaning to old ideas, such as embedded metadata, which are being reinvented with new Web technologies and tools to solve practical problems of resource discovery and navigation. "The Dublin Core" (and DCMI Metadata Terms) provides a solid basis for bridging these traditional and modern approaches, lookin at DC terms as a "small language for making a particular class of statements about resources". In this language terms are arranged into a simple pattern of statements and DCMI metadata properties are used as predicates in subject-predicate-object triples.

To describe this in a text form we may use the Turtle Syntax for RDF. In this syntax the triple will look like this:

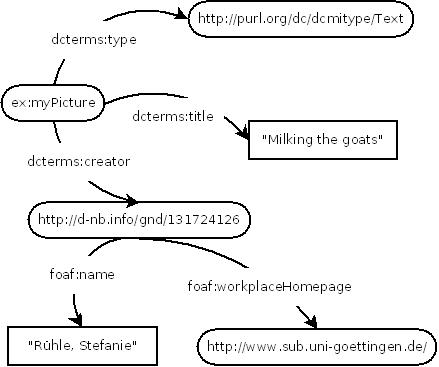

ex:myPicture dc:title "Milking the goats" ;

dc:creator <http://d-nb.info/gnd/131724126> .

<http://d-nb.info/gnd/131724126> foaf:name "Rühle, Stefanie" ; foaf:workplaceHomepage <http://www.sub.uni-goettingen.de/> .

In this example there are two statements about a picture:

- it has a title, which is „Milking the goats

- it has a creator, represented by the URI http://d-nb.info/gnd/131724126

and two statements about a person who created this picture:

- it's a link to the homepage of her workplace

- and her name

The object or value we use in the title statement is a simple string called a literal value. The value used in the creator statement is a non-literal value, a URI that leads to another metadata description, where the person who is the creator is described in a more detailed way - by her name and the homepage of her workplace. Though the statements we make about the person are not using Dublin Core properties they are non the less DC compatible, because in the namespace these terms are explicitly declared to be properties - one of the four metadata terms Dublin Core knows - and have been assigned a proper URI (see Dublin Core URIs and namespaces). This means we may use other properties than Dublin Core Terms as long as these terms are Dublin Core compatible. This way Dublin Core provides the grammar for a "metadata pidgin for digital tourists", a grammar that allows to merge terms from different vocabularies of different communities in one language and may be used to display both simple and complex issues. With this grammar Dublin Core provides a mechanism for extending the Dublin Core term set for additional resource discovery needs expecting that other communities will create and administer additional metadata sets, specialized for the need of their community.

Levels of Interoperability[edit]

Metadata is most helpful when used to navigate the information jungle of the Web -- to find, identify, use resources -- or to share and exchange structured information. However there is a tension between requirements of applications and of people:

- people prefer customized descriptions which reflect their understanding of the world

- applications need interoperability between descriptions in order to process them efficiently.

Metadata vocabularies help bridge this gap. Vocabularies define properties and classes that can be used to describe resources in a coherent way within or between communities. A vocabulary provides the shared basis for exchanging descriptions within groups of people. They support the interoperability of different metadata applications, and they support the ability of applications to change data with systems with no or minimal loss of information. The Dublin Core distinguishs four levels of interoperability. This User Guide is concerned with the first two of these levels:

- Level 1: Shared term definitions: At this level, a community uses the same classes and properties, for example DCMI Metadata Terms. CreatingMetadata supports this level of interoperability. But Level 1 interoperability is so open-ended that it quickly leads to a proliferation of custom-built solutions incompatible with each other, such as metadata expressed in document formats that require customized software to read and data models that cannot easily be mapped to generic, interoperable representations such as those expressed in RDF. Therefore this User Guide recommends to include Level 2 interoperbility.

- Level 2: Formal semantic interoperability: At this level, the description of resources is based on, or automatically mappable to, the shared formal model for metadata provided by W3C's Resource Description Framework (RDF), the basis of Linked Data. It's the sweet spot between ad-hoc implementations and shared models of records and constraints, which remain the object of experimentation and research. Given the state of play in 2010, implementers can design their metadata for compatibility Linked Data target with the confidence that this will ensure its formal compatibility with an explosively growing Cloud of Linked Data. - PublishingMetadata supports this level of interoperbility.

Users can explore the Dublin Core approach to shared record constraints (Levels 3 and 4) in the DCMI documents "Singapore Framework for Dublin Core Application Profiles", the draft "Description Set Profiles: A constraint language for Dublin Core Application Profiles", and the "Guidelines for Dublin Core Application Profiles". A well-developed example of an application profile developed according to these principles may be found in the "Scholarly Works Application Profile".