Living Sources in Lexical Description

Summary[edit]

Living Sources is an infrastructure for publishing scientific data. Various practical and theoretical issues arise when considering the publication of data (in contrast to the publication of results). Specifically, the assurance of persistence, quality control and scientific recognition of publicly available data are general problems, irrespective of scientific field of investigation. The Living Sources framework aims to offer an infrastructure that addresses these problems, so different fields of scientific inquiry can profit from the solutions proposed. The general plan of publishing data will be approached through a concrete case, namely the Living Sources in Lexical Description, an online peer-reviewed repository for the publication of dictionaries of the world's languages.

The Living Sources concept[edit]

Current situation[edit]

In contrast to the common practice of publishing and discussing research results, currently most scientists do not disclose the underlying research data. They do not make them available to a wider audience because of various reasons, like:

- failure to see wider applicability of data ("Why would anybody be interested in this?")

- insufficient quality (e.g. the data collection is not finished, it is not properly cross-checked, or the data is not complete)

- fear of plagiarism (others might not properly acknowledge the data)

- loss of control over interpretation (others might misunderstand the data, with undeserved blame being cast on the original creator of the data)

- loss of primacy of discovery (others might come up with important discoveries that the original creator also observed, but did not have time to work out and publish)

- lack of suitable publications to publish the data (most publishers are not interested to publish large tables with raw data)

- lack of technical knowledge how to make data available

- limited scientific recognition for making data available

All these - completely legitimate - reasons lead to the current situation in which data are mostly unavailable for inspection and scientific scrutiny, unavailable for reanalysis, and unavailable for meta-analysis. The goal of the Living Sources project is to provide an environment for the scientific publication of data that addresses these reservations. We envision that when more (raw) data will be publicly available, many new possibilities for research will become possible, both within disciplines but also across disciplines.

Prospects[edit]

Recent developments in computational infrastructure ("web 2.0") are showing the possibility for new kinds of information exchange. Living Sources will be an online repository of information created for and by scientists, tailored to the goals and needs of these scientists. To reach this goal, the concept of Living Sources will tackle problems that are of importance to many different fields of scientific inquiry:

- persistence of data (identification, storage and archiving)

- quality control ("peer review")

- scientific recognition and citability

The electronic format of publication offers various additional possibilities (not all of which will necessarily be implemented within the current project):

- incremental publications (e.g. adding corrections and additions, which is difficult for most traditional forms of publications)

- comments on and citation of individual data points (viz. micro-publication too small for traditional forms of publication)

- persistence of data through grid-like backup

- addition of digitized legacy material to supplement the newly published data

- open peer review schemes

Strategy[edit]

It is not the goal of Living Sources to force scientists to adapt to new paradigms of how to deal with data. It will function more as a service to those (sub)fields that have a need for data publication and dissemination. An instance of the Living Sources concept will be in need of:

- Availability of data with high level quality

- Support from scientists in the field

- An organisational board (for technical checks and organisation of field)

- Editorial boards and active engagement of scientists in the peer review (content check)

There are at least two complementary scenarios for the application of the Living Sources concept. First, the construction of a dedicated technical infrastructure which enhances the usability of data. This should be a "one stop shop" for scientists who look for a hosting environment, including all features needed for usage and deployment of such a system (including, e.g., user interfaces for editors, casual browsers and power users, searchability, persistent data storage, etc.). Second, Living Sources aims to set standards for the structure of data portals (like data journals or data archives) as for issues of citation and quality control. This is specifically geared towards groups of scientists who want to keep a strong hold on their data and can build their own systems, that are interoperable with any dedicated Living Sources infrastructure.

Separating publication from quality control[edit]

An important new possibility for scientific publishing, offered by the online electronic format, is that publication and quality control can be separated. In a publication system where each publication is costly, the quality control has to precede the physical publication. In contrast, in electronic form, the cost of each publication if small (the main costs relate to the up keeping of the overall system, not to the individual item published). This allows for a system in which publication itself (i.e "making available") can happen independent of the assessment of the quality ("peer review").

In the context of Living Sources, we would like to encourage people to publish ("make available") smaller amounts of data, or even incomplete data, to the (scientific) public. However, such small or incomplete data sets of course should be distinguished from large and finely annotated data collections. To allow for different kinds of publications, some kind of stratification is needed. This stratification of publication will happen through the peer review system. The data in Living Sources will be stratified in four different stages, compared here with traditional article publication:

| Stage | Scientific Status | Traditional Article | Public availability of traditional publications | Living Sources | Public availability in Living Sources |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Draft | Incomplete text | unavailable | Data in closed personal workspace | unavailable |

| 2 | Manuscript | Submission | unavailable | Data accessible to others | available |

| 3 | Self-publication | Submission | unavailable | Data technically validated | available |

| 4 | Scientific publication | Peer-reviewed paper | available | Data scientifically peer-reviewed | available |

There are two main differences between the structure of Living Sources and traditional scientific publication. First, the difference between Stage 2 ("manuscript") and Stage 3 ("self-publication") is newly added especially for Living Sources, and, second, the content in both these stages is openly available in Living Sources. In traditional publication format, these two stages are combined together as non-peer-reviewed manuscripts, which are normally not available to outsiders. In recent years, such manuscripts are made available more and more in the form of self-publication, either by using one's personal webpage, or a manuscript archive like arXiv.org or ling.auf.net/lingBuzz. In this sense, Living Sources is just following the current trend of making data available before it has been checked by peers.

The new distinction between Stage 2 and 3 becomes necessary because Living Sources has to deal with structured content that has to be computer-readable. In this context, it is of central importance to assure that the form of the publication is correct (e.g. right formatting, sufficient metadata, etc.). Only in a second step, the content of the data will be checked. To some extent, this distinction can be compared to a system in which traditional articles undergo two separate controls: one control which checks the spelling and grammar of the article, and judges whether the style is sufficient for the argumentation to be understood, and another control which checks whether the content is deemed interesting enough to be passed on to the rest of academia. Traditionally, these two checks are combined into the peer-review system (many journals will do the first check separately in the form of an editorial check, which prevents badly written articles to be passed on to the peer-review), which is not available to outsiders. For human-readable texts it is actually a good idea to restrict the amount of available texts in this way: there is already way to much text available for scientists to read. However, a large quantity of technically correctly published structured data is much easier to deal with. In the realm of data, excessive data is less of a problem than insufficient data.

[to be rephrased]

A very important consequence of this structure, that has to be clearly pointed out to possible content providers, is that data in Stage 2 ("manuscript" level) cannot be retracted anymore. Once it is made openly available, it is citable and has to be kept accessible for everybody. Of course, an author can make corrections. Or it might be possible to add a clearly visible sign to the data, for example saying that the author discovered that there is a potential flaw in the data, but does not have time/money/possibility to correct the error. All of this will happen openly, and that might scare some scientists. It will be part of the community building to explain this new openness to potential content providers.

Organisational structure[edit]

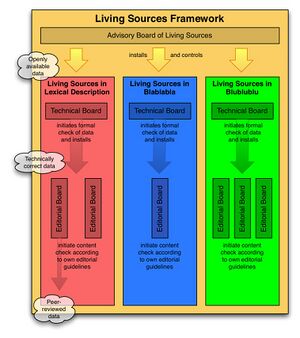

The framework of Living Sources will have three different kinds of official bodies:

- An Advisory Board for the whole framework of Living Sources

- A Technical Board for each instance of Living Sources, for example "Living Sources in Lexical Description" will have a technical board

- Editorial Boards for each peer review process within an instance of Living Sources

The framework of Living Sources is explicitly formulated to allow for expansion into different fields of scientific investigation. Each field will be able to start up its own instance of the Living Sources framework. The Advisory Board has the responsibility to oversee such expansion. Within the current project, only one instance of the Living Sources framework is initiated ("Living Sources in Lexical Description"), so the Advisory Board will not have many day-to-day obligations. However, when this first instance is successful, many other groups of scientist might follow. Already within the field of linguistic documentation and description there is a clear need for Living Sources instances like "Living Sources in Grammatical Description" or "Living Sources in Annotated Texts".

Any such instance of the Living Sources framework will need a Technical Board, which specifies the formal prerequisites for the data to be published in its context (i.e. what kind of data are allowed, what are the minimal requirements for the data, which metadata is needed, etc.). The Technical Board is also responsible for checking its own requirements. When a set of data meets these requirements, it has passed the formal phase of the quality control (cf. Stage 3 in the table above).

The next step of the quality control is a check of the content, which is performed by an Editorial Board. This board is in principle independent of the Technical Board, though there might be personal overlap. It is very well possible to have an instance of Living Sources without any Editorial Board, or to have multiple Editorial Boards alongside each other, with different criteria to evaluate the data. The Editorial Board function much like a traditional Editorial Board in scientific publication. It consists of a group of specialists from the field that write reports, or issue reports to be written by peers. Each Board sets its own quality criteria and decides on acceptance/rejections of any submissions. Simply being part of any Living Sources framework does not automatically imply that a particular Editorial Board has any prestige. Any Editorial Board will have to build its reputation among the content providers through the decisions they take.

Living Sources in Lexical Description[edit]

Scientific scope[edit]

The Living Sources in Lexical Description is the first implementation of the Living Sources framework. It is specifically geared towards the publication of dictionaries and other lexical resourced of the world's languages. Words are of prime interest to linguists and the general audience alike. Also, in the context of the recent movement in linguistics to recognize constructions (including both "set expressions" and "grammatical structures") as language-particular entities on a par with lexical items ("words"), the infrastructure for lexical resources can be expanded to a much larger scope of language description in the future.

Various branches of linguistics are interested in well-organized and cross-searchable lexical resources, like:

- Lexicography and terminology research

- Description and documentation of endangered languages

- Dialectology

- Ethnolinguistics

- Historical linguistics

- Computational linguistics

- Psycholinguistics

Yet, in the first phase of establishing Living Sources in Lexical Description, we will primarily focus on lexical resources of lesser studies and often endangered languages, offering specialists for such languages to publish their resources for which traditional publishers lack the needed publishing resources because the market is too small. The result of this disinterest is that many of the people working in the context of language documentation and description have a great amount of scientifically highly valuable lexical data that mostly does not leave their desks. Even if they are lucky enough to find a publisher for a dictionary, this will only be for very particular particular kind of data, namely not too little (as that will not make a nice book), nor too much (because that will not fit into a book). Also, because an offer to publish a dictionary will a one-time event (there is too little demand to allow for updated editions), there is a strong tendency to delay the publication as long as possible to make the dictionary as complete and error-free as possible.

Further, the necessity to linearly structure a printed dictionary forces researchers to organize dictionaries in ways that are not always suitable to find entries. In particular, entries are traditionally alphabetically ordered only for the primary languages, needing separate dictionaries for a search from the secondary language, or for searching a different string-order (e.g. reversed dictionaries for searching from the back of a word). Another example of the unsuitability of alphabetical ordering is a dictionary of a language with many prefixes. An alphabetical dictionary of such a language either forces the inclusion of words with prefixes under the heading of a headword, which makes it difficult to find a word for non-specialist. Or conversely, when ordered all separately, all versions of the same headword with different prefixes are difficult to find, making the dictionary far from perfect for more specialistic users. All these arguments show that the printed form is actually a particularly unsuitable format for a dictionary. The advantages of electronic dictionaries are long-known to lexicographers of the world's major languages, though online solutions for publications are normally not accessible for the lesser studies languages.

Also, the published lexical data will offer cross-searchability and cross-annotation, opening up new possibilities for comparative research, like the computer-assisted investigation of cognate words for historical comparison of the world's languages. Today, most historical-comparative research still involves hand-paging through dozens of published dictionaries to find entries that are hidden somewhere inside. To be able to do more comprehensive searches, or even to let dedicated computer algorithms suggest cognate sets, all available data has first to be entered by hand, or (when already available in electronic format) has to be converted with great effort into a consistent format.

Living Sources in Lexical Description will offer a better publication platform with much more flexibility, both as to the size of the data and their later extension or correction, and for searching and the application of more flexible ordering schemes.

Submission and Peer Review[edit]

For lexical data, we propose the following concrete implementation of the Living Sources concept. The first level of publication consist of submitted data without any checks. This data will be marked as "draft". When data has passed the first formal part of the review, it will be marked as "Words of the World". Such data consists of technically correct submissions that do not (yet) have been peer-reviewed as to the content. Peer review can (but need not) happen to obtain more scientific recognition, and (if successful) will lead to publication in a more prestigious series, like "Dictionaries of the World's Languages".

Step 1: Submission and bare publication[edit]

Submission of data leads to a formal check by the Technical Board. To allow of the easy submission of data, irrespective of scientific recognition, there will be a level of "bare" publication, with its own brand name for data that pass the formal check, but have not yet passed the scientific peer-review of the content.

- data is directly uploaded into a private workspace (in a first phase some technical assistance should be available, it is also possible in the future that content providers will directly work inside an online private workspace)

- from here, the data (or only a part of it) can be made publicly available by a simple click. The data then is formally published and cannot be retracted anymore.

- new data made available will be automatically evaluated by to Technical Board (this check can possibly be performed within the private workspace before the data is publicly available, if requested by the author)

- the technical check will be on formal issues and requirements only (data structure, metadata, terminology, preface, etc.)

- data that does not meet all technical requirements will still remain openly available, categorized as Draft

- these steps can be iterated until all technical requirements are met.

- data that passes the technical check will be announced as published in a special series, for example called Words of the World

Step 2: Peer-review of content[edit]

There can be different, independent, more prestigious series. Such series simply consist of an editorial board and an active community of peer-reviewers. If that particular scientific sub-community accepts a submission, it can give it's own "seal" of recognition by branding a special series. In the context of lexical data, one could think of series like "Dictionaries of the "World's Languages", "Intercontinental Dictionary Series", "Loanword Typology Wordlists", or "Cognate set collections". The branding and recognition of such series completely depend on the effort and success of the editors and the community or reviewers. Also the criteria to pass the review depend on the editorial board. Initially, only one such brand will be established, namely Dictionaries of the World's Languages.

- if wanted by the author, any technically accepted publication can be opened up for peer review to obtain more scientific recognition

- this peer-review should be time restricted and could even be openly available to the whole community ("open peer review"), though this is not necessary

- review should be a critical assessment of submission as a whole (i.e. commentary on the kind of collection, and on larger samples of submitted data points. For example, someone taking up the obligation to write a peer review will get a set of randomly sampled entries to evaluate. Only if more than a certain percentage needs correction, this will lead to rejection)

- comments on individual entries should be seen separate from commentary on the whole enterprise.

- individual errors/shortcomings can and should be corrected, but should not ban scientific recognition (except of course when the errors are too widespread).

- On the basis of the reviews, the editors decide on acceptance. After acceptance, the result will be a peer-reviewed dictionary, meaning "the principle of collecting and organising data is good, though there might be discussion about individual items". The submission is then published in the series called "Dictionaries of the World's Languages"

Step 3: Editions/Supplements[edit]

A central part of the Living Sources concept is that published data is changeable. Authors can add and correct data, but also users can add commentary or additional information to a published data set. Any such individual change or addition is never automatically part of the "seal" that was given to the publication. The "seal" of the peer-review only extends as far as the data that was originally submitted. Additions and corrections are categorized as "micro-publications", that add information to already available sources.

In principle, every micro-publication will be citable as an individual data point (see below), but in practice this is rather impractical, and will only be used in special circumstances. To get credit for many such micro-publications, any larger collections of such additions to the system can be submitted to review (we will not take individual micro-publications through to the review process). The idea is that once a particular author, or a user has added a lot of new information (i.e an author has added much information to his/her dictionary, or a user has collected many sets of cognates across different languages), such a collection of new information can be given to the scrutiny of the peers, resulting in either a new edition of an available publication, or a supplement to an available publication, or a completely new publication. Such substantially new version should count as publications worthy of being listed on a cv.

Scientific Recognition through Citation[edit]

A central aspect of scientific publication is the organization of scientific recognition. The prime tool to give recognition is science is proper citation. This means that the data in Living Sources in Lexical Description have to be citable to acknowledge each contribution. However, the citation format also has to be practically usable in the context of traditional articles and books (in linguistics, this means there has to be a short in-text citation format, and a more extensive format for the References section, which also should not span more than a few lines). Also, the status of data-publications for CV's has to be considered.

Citations of data in the context of Living Sources have clear parallels to the citation of traditional print media, but there are also some usages of the data that ask for new forms of citation. We distinguish between (at least) four different kinds of citations that people could use: citation of whole submissions, of individual data points, of micro-publications, and of complex collections of many data points originating from various publications. They are to some extent parallel to traditional forms of citation:

- whole submission ↔ book/article

- individual data points ↔ page in a book/article

- micro-publication ↔ personal communication

- collection of data points ↔ multi-author work

Some fictional examples follow, to illustrate how this could possible work (The structure of these example URIs is of course still unsettled.)

Citing whole submissions[edit]

The citation of whole submissions is completely parallel to traditional citation of books and articles. The submission has author, title and a submission data. The "Living Sources in Lexical Description" is like a publisher (though without physical location). The "stamp" is like a series, which might also have a serial number. As being online citations, they of course need a URL and a date. This might, for example, look like:

| Doe, John (2013) Dictionary of Nehali. [Dictionaries of the World's Languages, 3]. Living Sources in Lexical Description. (available online at livingsources.org/dictionaries/doe2013/, accessed on 23 March 2015). |

In-text citation likewise function as normal, e.g. (Doe 2013).

Citing individual data points[edit]

Often just one lexical entry will be cited, or individual points of information available in the databases. This is completely parallel to traditional citation of pages. Each data entity will have its own URI that can be referred to, so it will be possible to add in-text citations like (Doe 2013: foo). In the bibliography only the whole work will be cited, not the individual URI. The URI to the individual data point is a composite of both: "livingsources.org/dictionaries/doe2013/foo/"

| Doe, John (2013) Dictionary of Nehali. [Dictionaries of the World's Languages, 3]. Living Sources in Lexical Description. (available online at livingsources.org/dictionaries/doe2013/, accessed on 23 March 2015). |

Citing micro-publications[edit]

One more unusual situation that comes up in this new medium is the citation of individual comments that have been added by users to an entry, or be individual additions to fill in gaps of an already published source. Such micro-publications should probably be seen as alike to the tradition of "personal communication", meaning that they are cited in-text, but do not turn up in a bibliography. For example, consider the case of a discussion happening on the entry discussed previously (Doe 2013: foo). There are various comments posted in this discussion, and an in-text citation to one of them might look like this: (A. Ash 2015, commenting on Doe 2013: foo/talk/7). In the Bibliography, only the entry on (Doe 2013) turns up, and the link to the comment is like a page number, leading to the URI "livingsources.org/dictionaries/doe2013/foo/talk/7".

| Doe, John (2013) Dictionary of Nehali. [Dictionaries of the World's Languages, 3]. Living Sources in Lexical Description. (available online at livingsources.org/dictionaries/doe2013/, accessed on 23 March 2015). |

Likewise, if, for example, a native speaker would like to add individual words to a published dictionary of his language, such entries could be added on a one-by-one basis, and the citations would work just like comments, e.g. (E. Bare 2014, supplementing Doe 2013: fooxt). If such a person has been adding a lot of new information, he or she might consider submitting the whole collection of additions as a separate publication.

Citing complex collections of data point[edit]

One of the main advantages of electronic resources is the possibility to search for data, possibly resulting in a selection of data cross-secting multiply submissions. It is very important to have a good system for citing such usage of large data sets. The closest parallel in traditional citation is citing a multi-author publication. Probably, such citation will work as follows. After creation of a custom data set (e.g. through search and subsequent hand-picked selection), this data set can be saved online, resulting in a URI for the saved data set (e.g. livingsources.org/users/ArthurAsh/savesets/35). With the saved data set comes a receipt that counts the number of selected data points per author, e.g. John Doe (243), Michael Cysouw (67), Sonia Ash (12), D.H.M Broom (2). The receipt will then suggest various ways to cite the data. In this example, it might be best to cite John Doe separately, because the large majority of the data comes from his submissions. In the citation of this multi-authored publication, the authors might be ordered according to the amount of data points, and the date would be the date of the saving of the collection. The citation in the bibliography should list all authors, and might look like:

| Doe, John, Michael Cysouw, Sonia Ash, D.H.M. Broom (2015) Custom data collection. Living Sources in Lexical Description. (available at livingsources.org/users/ArthurAsh/savesets/35). |

The form of in text citation might looke like: (Doe et al. 2015), or maybe like: (Doe, Cysouw, Ash et al. 2015), depending on editorial guidelines about citing multi-author works. Maybe we will suggest a new abbreviation, like "agg." (for "aggregated), so the citation would look like (Doe, Cysouw, Ashh agg. 2015). The details of such problems will have to be discussed with editors of traditional journals, and with the content providers.

Practical Organisation[edit]

Submission format[edit]

Submissions should consist first and foremost of the data itself in a suitable format (concrete decisions are still open on the details of the format) with a set of supplementary material ("metadata"). This supplementary material can be considered to be some kind of preface to the data. First, there should be various texts describing the data, addressing at least the following issues:

- general information on the language (e.g. fieldwork location, number of speakers, sociolinguistic situation, etc.)

- scientific background/research field of researcher

- editorial background/rationale of the collection of the data

- selection criteria for entries (e.g. sampling, semantic fields, wordlists, etc.)

- process/method of data collection

Second, there should be various structured documents describing the structure of the data:

- description of data categories used

- specification of orthography used

- specification of terminology used

There might be various other kinds of metadata that will be requested, either by the Technical Board, or by an Editorial Board, as part of their editorial policy.

Social infrastructure[edit]

The various boards will have to be filled with both some high-profile researchers from the field, but also with some committed (younger) colleagues that will do most of the practical work. At the start of the project, these board will need to spell out many of the details of the working of the framework, like encoding formats and review practicalities. There will need to be an

- Advisory Board for the whole Living Sources infrastructure

- Technical Board for Living Sources in Lexical Description

- Editorial Board for Dictionaries of the world's languages

Then it will be important to communicate this project to prospective content providers. We plan to organize workshops at conferences to present the framework and discuss its possibilities and shortcomings with people from the field. We will also invite possible participants to meet at local meetings with the developers to flesh out issues with the data itself and with the data formats intended for submission. In this way, we hope to have a large enough body of high quality submissions in the pipeline at the end of the currently applied funding to sustain the visibility of the project through regularly data releases.

Another central point of discussion with the field will be the establishment of citation standards and practices for CV-listing of submitted data. Such discussion should ideally result in guidelines being published by professional bodies, like the DGfS or the LSA.

Technical infrastructure[edit]

There are many technical issues that will have to be worked out in detail in the first phase of the project.

- Encoding formats

- Data structure of the framework

- Import facilities from community formats (e.g. Toolbox)

- Webservices, "command-line" expert access, API for outside access

- How to search the data, e.g. both a "graph" search (mediated by approximate translational equivalents) or "string" (mediated by approximate orthographical equivalents)

- Online editing, and uploading of new version (including diff-check)

- Structure and granularity of unique identifiers for all data objects

- Direct reusability of data in local offline databases (e.g. helping people to link their offline ACCESS/Filemaker databases to our online repository, or allow personal copies of Living Sources for offline usage)

- Formats for third party commentaries

- Formats for orthography profiles

- Formats to structurally capture the terminology used

- peer review infrastructure (e.g. sampling methods to randomly select data to be checked)

Persistence of data[edit]

A central part of the planned organization is to uniquely identify every word that is submitted to the Living Sources infrastructure through a stable URI. In this way, other users (be it databases or human investigators) can more clearly and readily refer to a particular word. These URI and their content will be stored securely through grid-backup, and there will be a long-term archiving strategy. More importantly in the nearer future will be sustainability of the infrastructure, so it can be used by scientists. This projects aims for a first initiative through the MPG to fund and host the Living Sources infrastructure. However, given the current activity on behalf of various funding agencies (DFG, NSF) that data collected during their funding has to be made publicly available, we expect that already in the near future it might be possible to engage these agencies in funding the upkeeping of the framework (as long as enough funded projects produce data that can be submitted to Living Sources).

Content providers[edit]

In this first phase, we will only consider lexical data on lesser studied languages. We will actively engage the following content providers to submit data. Others are of course welcome when they become interested.

- Fieldworkers attached to MPI-EVA (Leipzig) and MPI for Psycholinguistics (Nijmegen)

- Intercontinental Dictionary Series (Leipzig)

- Loanword Typology Project (Leipzig)

Rights[edit]

All data in any Living Sources instance will be completely open access. The different stages of publication (Draft, Words of the World, Dictionaries of the World's Languages) will probably all need their own License, a decision that has to be taken by the various Boards of the framework. In general, all copyright remains completely with the author of the data - there will be only non-exclusive copyright transfer. Probably at every stage of publication, there will be an agreement between the authors and Living Sources that Living Sources has the rights (to store) and distribute the data under the Creative Commons License.

Application[edit]

This initiative is planned as a three-year project, running from 01.07.09 until 31.06.2012.

Work Schedule[edit]

Phase 0: Preparations[edit]

from funding decision until projected start date of project on 31.06.09

- recruiting of staff, setting up of offices

- community building: presentation and discussion of project at DoBeS meeting (a primary source of contributors)

- constitutions of boards:

- Advisory Board for the overarching framework of Living Sources

- Technical Board for Living Sources in Lexical Description

- Editorial Board for Dictionaries of the World's Languages

Phase 1: Concepts and Functional Specification[edit]

6 months: from 01.07.09 to 31.12.09

- The various Board develop policies and concrete specifications for submissions and review

- Continue community building

- Agreement on encoding standards and metadata requirements

- Analysis of use cases and formulation of functional requirements for underlying framework

- Draft prototype of framework

- Functional specification and draft version of Graphical User Interface

Phase 2a: Prototype Implementation[edit]

12 months: from 01.01.10 to 31.12.10

- Linking framework and GUI

- Adding functions for content evaluation, according to the specification as formulated by the Boards

- Adding data import/export functionality (ingestion, upload, conversion, versioning, download)

- Adding Web 2.0 functionality (user profiles, annotations, discussion)

- Adding citation structure (notes to users, receipts of downloads, custom save-sets)

Phase 2b: Final Implementation[edit]

6 months: from 01.01.11 to 31.06.11

- Testing and validation

- Additions based on requests from beta-users

- Possibly inclusion of mirror of data from other data-repositories

- Possibly inclusion of special output formats, e.g. suitable for printing, or for websites

- Possible inclusion of offline personal workspace (e.g. using offline browser functions like Google Gears)

Phase 3: Data Ingestion[edit]

12 months: from 01.07.11 to 31.06.12

- Marketing and dissemination of project to content providers and users

- Assistance with the first batch of ingestion of data

- Publication of guidelines and recommendations for content providers, users (both individuals and institutional, e.g. traditional journals), and funding agencies.

- Sustainability: organization of further financing of the framework and the data already ingested

Staff[edit]

- 1 Lexical Curator (TVöD E 13): 58.000 EUR p.a.

- 2 Infrastructure Programmers (2 x TVöD E 10): 2 x 48.800 EUR p.a.

- 1 Linguistic Assistant/PhD-student (TVöD E13/2): 23.300 EUR p.a.

- 2 Student Assistants (19 hours/week, one from linguistics and one from computer science): 2 x 8.500 EUR p.a.

Total 195.900 EUR p.a.

Expenses[edit]

- Dedicated development server (automatically covered by MPDL ???)

- Offices for staff (automatically covered by MPDL ???)

- Travel expenses for staff and visitors (EUR 10.000 per year)

This project depends to a large extent on the communication and cooperation with various partners, both developers at the MPDL in Munich and Berlin and at the MPIs in Leipzig and Nijmegen, as well as editors and content providers throughout the world. Success of this project strongly depends on regular meetings between the staff of the current project and these partners. To ensure this communication, we plan the following travel expenses:

- Visits to Nijmegen, Leipzig, Berlin and München to coordinate efforts with local developments (3 regional persons/trips per quarter, train and housing à 250,- = total 3.000,-per year)

- Visits to meetings of scientific community (conferences, workshops) to present and discuss the project (2 international persons/trips per year, flight and housing à 1.000,- = total 2.000,- per year)

- Workshops for community building (1 workshop per year, covering travel and housing for 5-10 international participants from outside the MPG à 5000,- = total 5.000,- per year)

Scientific Support within MPG[edit]

[Note: This is list is for planning only; not all of these people are contacted yet!]

MPG Directors

- Bernard Comrie/Martin Haspelmath (MPI-EVA Leipzig)

- Steve Levinson (MPI Psycholinguistics Nijmegen)

- Wolfgang Klein (MPI Psycholinguistics Nijmegen)

- Mike Tomasello/Elena Lieven (MPI-EVA Leipzig)

- Mark Stoneking (MPI-EVA Leipzig)

- Jürgen Renn (MPI History of Sciences Berlin)

- Jürgen Jost (MPI MiS Leipzig)

MPG Nachwuchsgruppenleiter

- Ina Bornkessel (MPI-CBS Leipzig)

- Michael Dunn (MPI Psycholinguistics Nijmegen)

- Brigitte Pakendorf (MPI-EVA Leipzig)

Cooperation[edit]

- DoBeS

- EMELD

- SIL

- DELAMAN

- LinguistList

Other Support[edit]

Potential subsidiary financial support:

- ESF call BABEL

- Volkswagenstiftung

- Heinz-Nixdorf-Stiftung

Subsidiary Information[edit]

The following information is not directly intended to end up in the application. It is just collected here for future reference.

Slides of meetings

On 30 September/1 October 2008 we had a meeting at the MPDL offices in Berlin to talk about a first draft of the application. These are a few of the slides that were presented to focus the discussion.

- Michael Cysouw File:Cysouw.pdf

- Dafydd Gibbon File:Gibbon.pdf

- Jeff Good File:Good.pdf

- Nikolaus Himmelmann File:Himmelmann.ppt

- Frank Seifart File:Seifart.doc